Verbal abuse would not decide one Criminal Justice: Corrections student’s fate

Ricardo Covarrubias was used to being told he couldn’t do something, that he wasn’t capable or smart enough. “My whole life I had people telling me I wasn’t going to be anything,” says Ricardo. It started from an early age and took root in his psyche.

“Teachers in my high school were telling me I’m going to be like every Mexican doing concrete, construction or being a painter or landscaper,” he remembers. “In my eyes I thought teachers were supposed to boost your confidence, not bring you down.”

Ricardo has some physical scars along with the emotional ones. He had dreams of a career in the NFL before a severe leg injury took him off the football team and nearly broke his spirit for achieving anything. “I fell into a dark place; I didn’t know if I would ever walk again.”

He started reading his bible and fervently exercising his slowly withering leg with the help of his mom, Elida, his dad Raul, and his three siblings. “I would walk holding onto the wall with my mom, dad, brother or sister holding me up on the other side. I knew I was never going to be my normal self again.”

He thought about quitting school. “I told my mom I was never going to graduate anyway,” says Ricardo. No one in his family had ever graduated from high school. “But as a son, you don’t want to see your mother hurt.”

“I was just sitting there embarrassed, spiraling down,” he remembers. But something reached deep inside him and pushed him back up toward the surface. “I told myself nobody can tell me what I’m capable of doing. I wanted one more shot to prove those (other) guys wrong.”

It took almost a year for Ricardo’s leg to heal at about 80% function. Three years later there was no noticeable limp as he walked across the stage of his high school graduation ceremony distinguished by his 4.0 GPA.

Ricardo shook his high school principal’s hand and received his diploma before continuing the line to shake the hand of another school representative – one who had once told Ricardo he was ‘never going to be anything’ in his life.

Ricardo remembers that moment clearly. “Oh, you actually made it,” he says to me. “Yes, and I’m going to college,” Ricardo answered. “We’ll see about that,” came the response.

Ricardo smiled and walked away. “I don’t hold grudges anymore,” he says. “I’m never going to let other people tell me what kind of person I am. I love it when people tell me they doubt me, because I love to prove them wrong.”

He spent some time searching for a career match and the education that would get him there. He was attending community college and thought he felt a strong pull toward law enforcement.

“Suddenly SJVC kept popping up on Facebook, twitter, everywhere, and I was like, ‘hmmm a Registered Nurse. “I love helping people and seeing the looks (gratitude) on their faces,” he says. But then working with juveniles on probation caught his attention. He made the call and an appointment to visit the campus and check out the Criminal Justice: Corrections program.

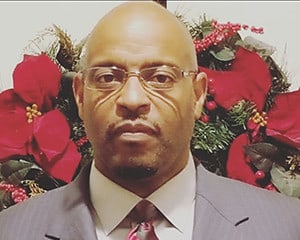

“I talked to Mr. Martin (Criminal Justice: Corrections, Program Director for SJVC’s Modesto campus) and he asked me lots of questions. Then he got right to the point. He told me, ‘You will wear a uniform every day, you will train every day.’ “And he saw the potential in me; he saw that I had the attitude and the demeanor.” Two weeks later Ricardo enrolled in the CJC program and didn’t look back.

But he did look at his reflection in the mirror. “When I saw myself in the SJVC (Criminal Justice: Corrections) uniform, I got everything back. I got the fire back, like when I was in sports,” says Ricardo.

The program was exactly what Ricardo hoped it might be. Three months in, he was on his game. The discipline, physical strength and agility requirements, law enforcement rules and regulations, take-down methodologies and life-saving techniques met a ready student. “Everything there came easy to me and it stuck,” he says.

Suddenly, it was all at risk. Ricardo and his fiancé, Rosey, were living together and expecting their first child, when it was going to become necessary for her to leave her job. Ricardo went to Mr. Martin to tell him he might have to drop out of school. “Why are you here?”, Ricardo remembers Mr. Martin asking. “Why ARE you here?” he repeated. “I told him I want to better myself, to be somebody that nobody thought I could be.” says Ricardo. “He told me, ‘Then do it.’” And, Donald Martin and program staff and faculty would do all they could to lend support.

Ricardo would try to hang on. With every sacrifice comes great reward. “Mr. Martin would tell me that. If I couldn’t get to school, he took the time and made the effort to cover everything I’d missed that day. If I came in really physically sick, he would say, ‘What are you doing here?’. “Sometimes he sent a text message: You are a great student! “I finally had someone who believed in me.”

“Ricardo would ask questions so in depth or seeking more as to ‘why?’ or ‘how?’, says Donald Martin, CJC Program Director. “Many of his classmates came to me in private and felt thankful he asked those, as they never would have progressed that far over an issue.”

Before CJC students graduate Donald Martin invites representatives of several law enforcement agencies, sheriff’s offices and correctional facilities to visit his program and speak to his students about their facilities and possible recruitment among his well-trained cadets. “He got Humboldt County to come look at me, and others to come look at me. I owe my whole career to him, to be honest,” says Ricardo.

Ricardo graduated from San Joaquin Valley College’s Criminal Justice: Corrections program in November with a 4.0 GPA. Another first for his family. He immediately went to work as a Correctional Officer for a County lock-up facility currently housing 121 inmates. He is responsible for helping to maintain the safety and security of the facility, staff and incarcerated population.

“It’s different every day,” says Ricardo. “There’s nothing easy about this job, and we can never get complacent. Safety is always first. There are routines, but routine doesn’t mean relaxed. People can get hurt.”

Respect is the currency that determines the level of peace and cooperation that might exist. “You earn respect here, you don’t just get it,” says Ricardo. “I don’t judge them (inmates) for who they are; I don’t judge them for their crimes. My job is to protect their safety and well-being around other inmates. I treat everybody equally; I say, ‘yes sir’, ‘no sir’ to them. I talk to them like humans.”

This is the career Ricardo imagined for himself. “I don’t see myself doing anything else. I loved the program (CJC) and I love what I do now.”

“Ricardo really was one of the best ever here,” says Martin. “He put so much into learning about so many aspects of the field. Ricardo’s knowledge and skills amazed his field training officers.”

He wants to pass along a little of what he has learned to others who might be searching, testing new ground to stand on. He finds an opportunity when Mr. Martin invites him to address a new CJC class and share with them his journey from sitting in their seat to the career he now enjoys.

“I ask them, ‘Why are you here?’. ‘Why ARE you here?’ Ricardo feels he learned from the master.

Learn More About A Career In Criminal Justice: Corrections

Criminal Justice: Corrections can open doors to work in private, state, federal prisons or local jails as well as in private security in California. Learn how to join this exciting career and why you should pursue a correctional officer degree.

You might also like

More stories about

Request Information

All fields using an asterik (*) are required.